Crystal Palace

Sir Joseph Paxton, 1850-1851

Overview

About This Work

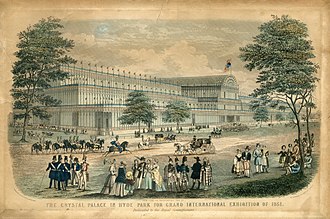

The Crystal Palace was a revolutionary architectural structure designed by Sir Joseph Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London. Built in just five months, the colossal temporary building was a masterpiece of Victorian engineering, measuring 1,848 feet (564 metres) long and covering 19 acres—three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral. It was constructed almost entirely from prefabricated cast iron and plate glass, earning its name from Punch magazine. The building was not just a venue but the exhibition's primary exhibit, symbolizing the industrial and imperial might of Britain. After the exhibition closed, the structure was dismantled and rebuilt (in an enlarged and permanent form) at Sydenham Hill in South London, where it stood until it was destroyed by fire in 1936.