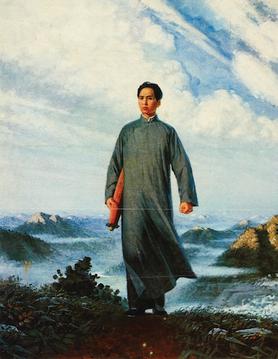

Chairman Mao en route to Anyuan

Liu Cunxia, 1967

Overview

About This Work

Chairman Mao En Route to Anyuan (1967) is arguably the most reproduced painting in human history, with estimates suggesting over 900 million copies distributed globally. Painted by Liu Chunhua, a 23-year-old member of the Red Guard and student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, the work measures 76 × 55 cm (oil on canvas). It depicts Mao Zedong at approximately age 29, striding across a mountain peak in traditional Chinese dress, umbrella tucked under his arm, one hand clenched in a revolutionary fist, his face resolute and visionary as he gazes into the distance. The painting commemorates Mao's legendary 1921 journey to Anyuan, a coal-mining region in Jiangxi Province, where he allegedly organized the first major workers' strike in China—a moment revised and elevated by Communist Party historiography. Painted during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the work represents the apex of socialist realism as a propaganda medium in Communist China. It was created for the 1967 exhibition "Mao Zedong's Thought Illuminates the Anyuan Workers Movement" and was explicitly promoted by Jiang Qing (Mao's wife) as an official "model work," the visual counterpart to the revolutionary operas and ballets she endorsed. The painting functions as both artwork and instrument of state ideology, crystallizing the "cult of Mao" at the height of the Cultural Revolution.