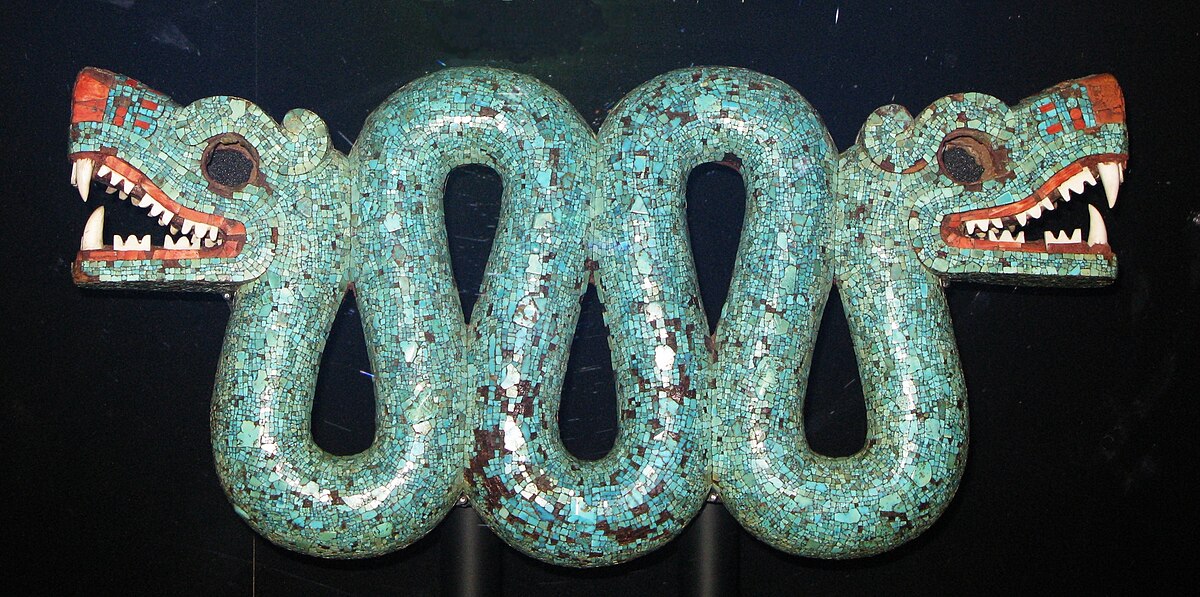

Double-headed Serpent

Unknown (Aztec), 1400-1521

Overview

About This Work

The Double-Headed Serpent is an Aztec (Mexica) sculptural mosaic, dating to the 15th–early 16th century CE, now held in the British Museum in London. Measuring 20.5 x 43.3 x 5.9 cm, it is constructed from Spanish cedar wood covered with an intricate mosaic of over 2,000 turquoise tesserae, with red and white shell detailing the mouths, gums, and teeth of the two serpent heads. The sculpture was likely worn across the chest as a pectoral ornament during religious ceremonies, possibly by a high priest or the tlatoani (ruler) himself. The serpent form is deeply symbolic in Mesoamerican iconography, representing divine power, cosmic duality, and the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl. It may have been among the treasures sent to the Spanish King Charles V by Hernán Cortés following the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1519–1521. The object exemplifies the extraordinary skill of Aztec lapidary artists (those who work with precious stones) and stands as one of the finest surviving examples of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican art.