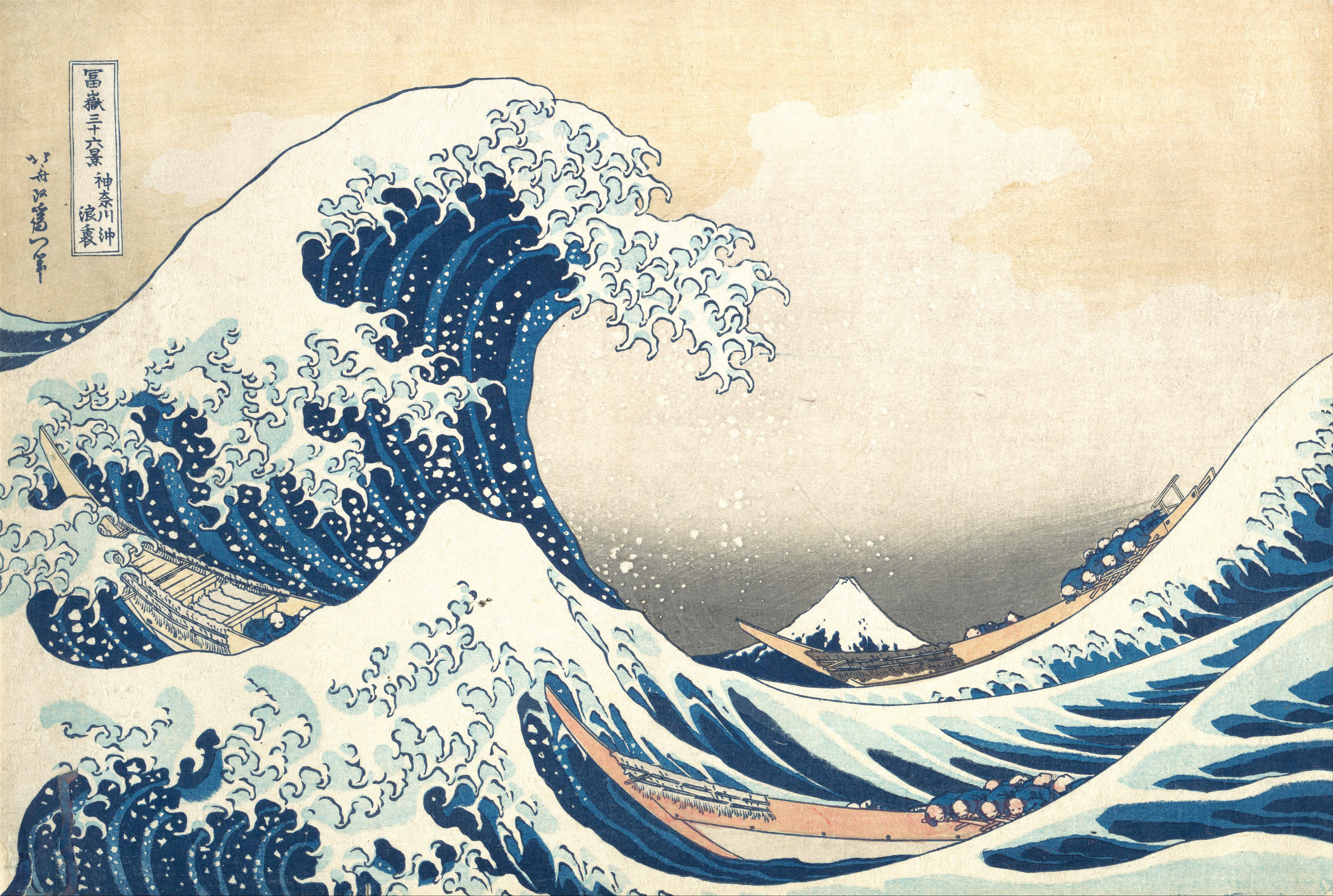

The Great Wave

Hokusai, c.1830

NatureNon-Western

Overview

About This Work

The Great Wave off Kanagawa is the most famous work from Hokusai's series "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji" (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), published c. 1830–1832. The woodblock print depicts three boats caught beneath a towering wave with Mount Fuji visible in the distance. It measures approximately 25.7 × 37.9 cm and exists in multiple impressions across museum collections worldwide. The print exemplifies the ukiyo-e ("pictures of the floating world") tradition while demonstrating Hokusai's innovative synthesis of Japanese and Western artistic techniques.

Visual Analysis

Composition

The composition creates a dramatic tension between the enormous wave and the distant, diminutive Mount Fuji. The wave forms a sweeping diagonal that dominates the left side of the image, its claw-like foam reaching toward the sacred mountain.

The boats and their crews are rendered small against nature's power, emphasizing human vulnerability. The asymmetrical balance—heavy wave versus distant mountain—creates dynamic energy while maintaining visual equilibrium.

Hokusai employs the Western technique of linear perspective (learned from Dutch prints) while maintaining the flat, decorative qualities of traditional Japanese art.

Colour & Light

The print uses a limited palette dominated by Prussian blue (Berlin blue), a synthetic pigment recently imported to Japan from Europe. This creates the distinctive deep blue of the wave and sky.

Gradations from dark blue at the wave's crest to pale blue in the sky create atmospheric depth. The white foam and pale yellow sky provide contrast, while the boats' ochre tones add warmth.

The flat color areas characteristic of woodblock printing are enlivened by subtle gradations achieved through the bokashi technique (gradual ink application).

Materials & Technique

The print was created using the traditional Japanese woodblock (mokuhanga) technique. The process required multiple carved wooden blocks—one for each color—printed in sequence onto handmade paper.

The publisher Nishimura Eijudō produced multiple editions. Early impressions show richer colors and sharper detail; later printings often appear faded or lack subtle gradations.

The carving required extraordinary precision—note the delicate foam "fingers" at the wave's crest, each requiring careful cutting of the woodblock.

Historical Context

Context

Hokusai created this print in his early seventies, at the height of his artistic powers. The "Thirty-six Views" series (eventually expanded to 46 prints) capitalized on several contemporary trends: the popularity of Mount Fuji as a pilgrimage destination, improved roads enabling domestic tourism, and public fascination with landscape imagery.

The newly available Prussian blue pigment enabled the print's distinctive coloring. This synthetic pigment, more stable and vibrant than traditional indigo, transformed Japanese printmaking aesthetics.

Japan remained largely isolated under Tokugawa shogunate policies, yet Dutch trade at Nagasaki allowed limited cultural exchange. Hokusai studied Western perspective techniques through Dutch prints, creating a hybrid visual language.

Key Themes

Nature's Power and Human Vulnerability

The print presents nature as an overwhelming force. The wave towers over the boats, its foam suggesting grasping claws. Yet the fishermen continue their work—human resilience amid natural power.

Mount Fuji, sacred in Shinto belief, appears small and distant yet perfectly stable. The mountain's permanence contrasts with the wave's momentary violence—the eternal versus the transient.

This tension between human activity and natural forces resonates with the ukiyo-e tradition's interest in the "floating world"—the Buddhist-influenced awareness of life's impermanence.

Exam Focus Points

Critical Perspectives

The print's influence on Western art was profound. After Japan opened to trade in 1853, ukiyo-e prints flooded European markets. Artists including Monet, Van Gogh, and Whistler collected Japanese prints; the resulting "Japonisme" movement transformed Western aesthetics.

Modern scholars debate whether Hokusai intended symbolic meaning (nature overwhelming humanity, the sacred mountain enduring) or primarily aesthetic impact. The print's ambiguity enables multiple readings.

Questions of authenticity arise from the print medium itself—which "original" is definitive when thousands of impressions exist? This challenges Western assumptions about unique artistic authorship.

Post-colonial readings examine how Western reception emphasized the print's "exotic" qualities while overlooking its sophistication—a pattern of Orientalist appropriation.