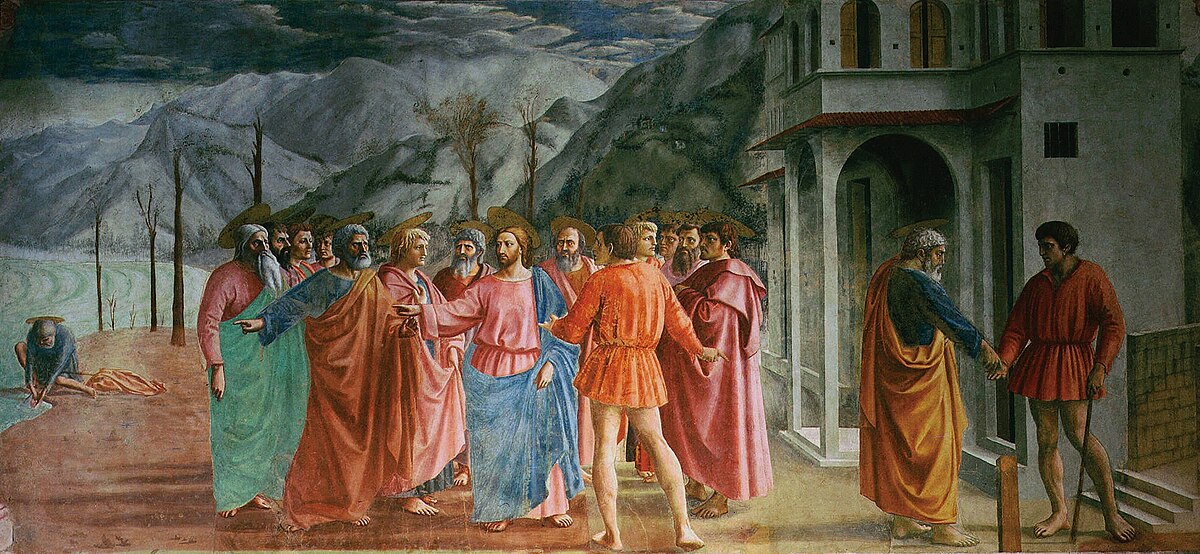

Tribute Money

Masaccio, c.1425

Overview

About This Work

Tribute Money is a fresco by the Florentine painter Masaccio (1401–1428), located in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. Painted between 1425 and 1427, it is one of the foundational masterpieces of the Italian Early Renaissance. Measuring 8 feet 1 inch by 19 feet 7 inches, it depicts a narrative from the Gospel of Matthew (17:24–27), in which Jesus instructs the apostle Peter to find a coin in the mouth of a fish to pay the temple tax. The fresco revolutionized painting through its systematic use of linear perspective, chiaroscuro (the modeling of light and shadow), and atmospheric perspective—techniques that would define the Renaissance. Although Masaccio died at age 26, this single chapel became a pilgrimage site for generations of artists seeking to understand how to paint space, light, and the human form. For Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, the Brancacci Chapel was a masterclass in anatomy and perspective that no academy could provide.