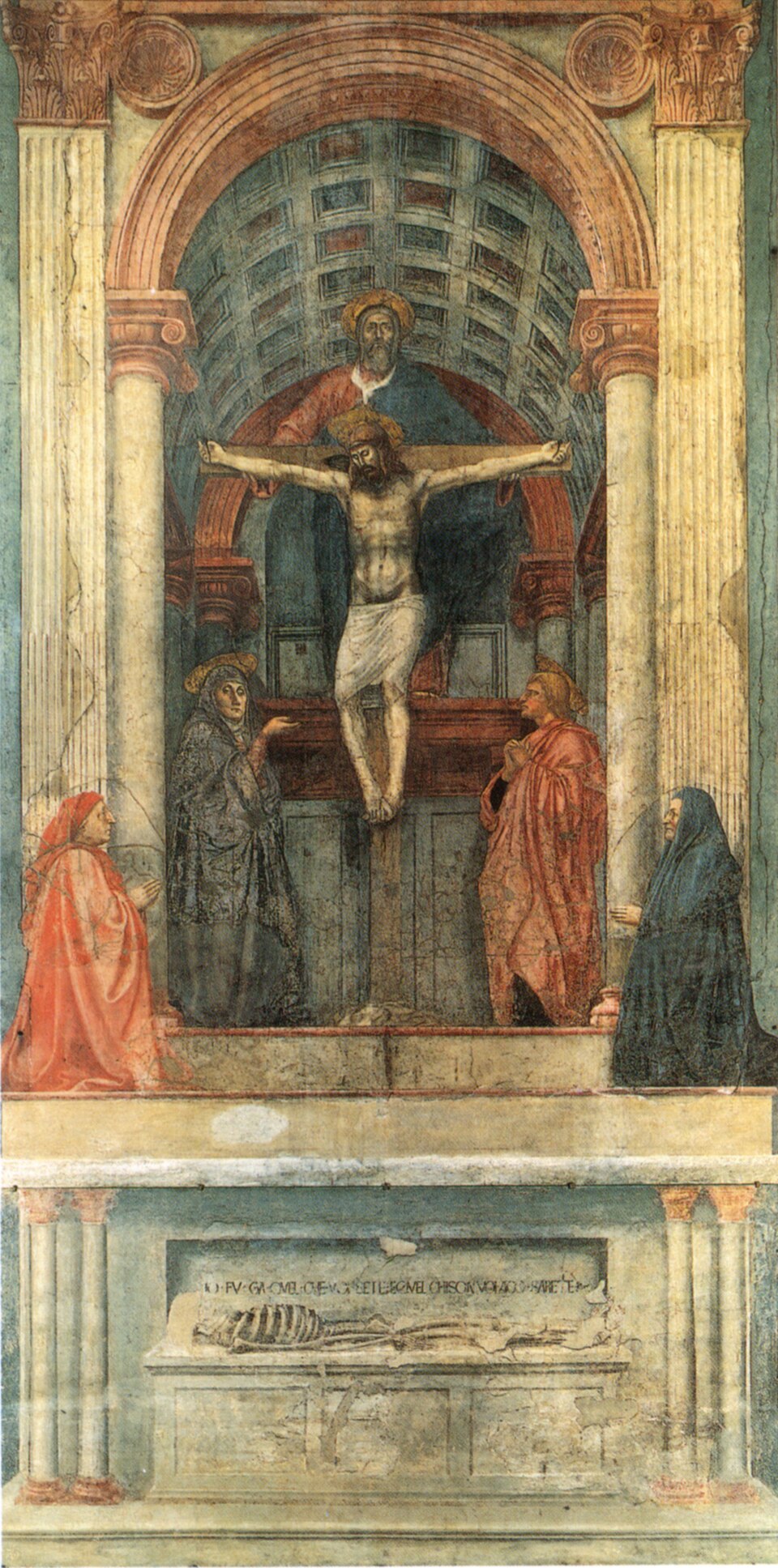

The Architectural Frame: The composition is framed by a Roman triumphal arch, a classical reference that symbolizes Christ's triumph over death and sin. The arch itself is painted with perfect architectural detail—fluted columns, a coffered entablature, and capitals rendered with precise classical proportions. This is not mere decoration; it is part of Masaccio's larger claim that the Classical world and Christian theology are united in a rational, intelligible order. The arch frames a barrel-vaulted niche, a semi-cylindrical recession of space that appears to extend several metres behind the picture plane.

The Vanishing Point: Masaccio placed the vanishing point at the base of the crucifix, precisely at the eye level of the kneeling donors. All orthogonal lines—the receding edges of the barrel vault's coffered ceiling—converge toward this single point. This creates the optical illusion that the viewer is standing at ground level, looking upward into a real architectural space. The mathematical precision is extraordinary: modern analysis shows Masaccio's recession calculations to be accurate to within two parts in one thousand.

The most visible expression of this perspective is the coffered barrel vault above the crucifix. The square coffers and circular rosettes diminish in size and compress in depth as they recede. Each coffer is slightly smaller than the one in front of it, following a mathematical progression. Vasari famously wrote that the vault looked so convincing "there seems to be a hole in the wall"—a perfect description of how successfully Masaccio created the illusion of three-dimensional depth.

The Trinity: Within the vaulted niche are the three figures of the Trinity: God the Father stands behind the crucifix, His massive arms outstretched to embrace the cross, looking directly at the viewer with piercing eyes. Christ on the Cross is anatomically accurate, physically vulnerable, and deeply human—His musculature rendered with careful chiaroscuro. The Holy Spirit appears as a white dove hovering above the cross.

The Witnesses: The Virgin Mary stands on the left in traditional blue robes, her face expressing sorrow as she looks directly at the viewer. Saint John the Evangelist stands on the right, contemplative and withdrawn. Both are rendered with human dignity and psychological depth.

The Donors: Below the crucifix, two figures kneel in prayer—the patrons who commissioned the fresco, likely Domenico Lenzi and his wife. Their contemporary Florentine dress and profile positioning suggest posthumous portraits, ensuring their perpetual spiritual presence.

The Memento Mori: Beneath the painted altar lies a skeleton in a marble sarcophagus with the Latin inscription: "IO FUI GIA QUEL CHE VOI SIETE E QUEL CH'I SONO VOI ANCO[R] SARETE" ("I was once what you are and what I am you also will be").