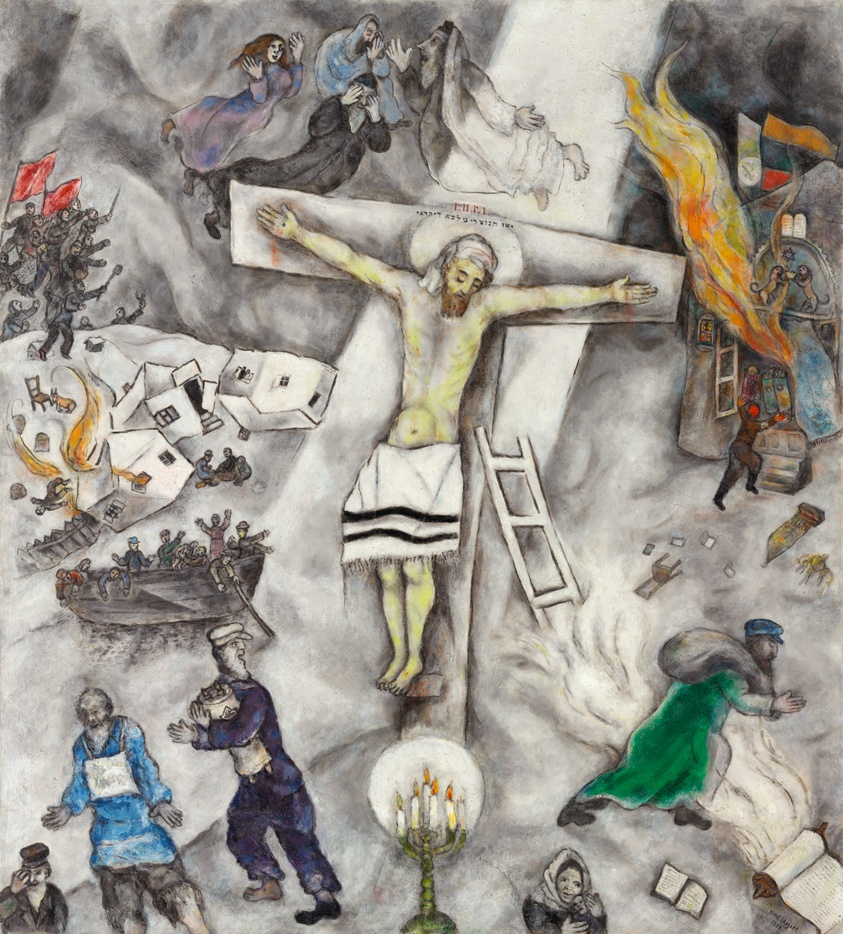

White Crucifixion

Marc Chagall, 1938

Overview

About This Work

White Crucifixion (1938) is one of the most powerful and historically significant paintings of the 20th century. Created by Marc Chagall (1887–1985), a Belarusian-French Jewish artist, the work measures 155 x 139.7 cm (oil on canvas) and is housed in the Art Institute of Chicago. Painted in the autumn of 1938—the year of Kristallnacht (November 9–10, when Nazi brownshirts destroyed Jewish businesses and synagogues across Germany)—the painting represents Chagall's first major artwork depicting Christ as an explicitly Jewish figure. Rather than the traditional loincloth, Christ is wrapped in a white prayer shawl (tallit); his crown of thorns is replaced with a simple headcloth. Surrounding this central crucifix are scenes of Jewish persecution: burning synagogues, fleeing refugees, destroyed Torah scrolls, and a menorah (Jewish candelabrum) glowing at the foot of the cross. Above the cross, Old Testament patriarchs and matriarchs weep and mourn. The painting is a direct condemnation of Nazi anti-Semitism and functions as a visual elegy for European Jewry on the eve of the Holocaust. It represents Chagall's most explicit assertion of Jewish identity and his most powerful statement about the identification of Jewish suffering with the suffering of Christ.