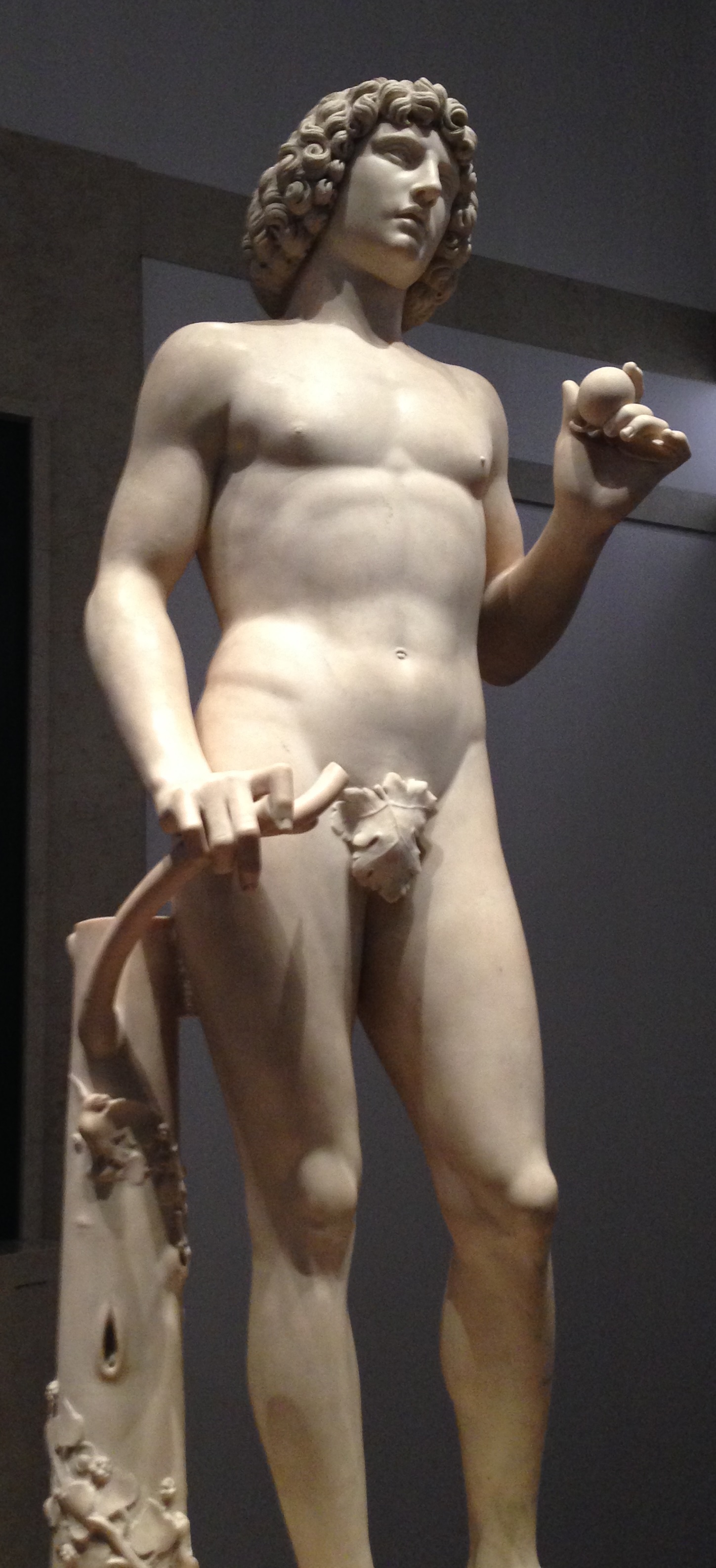

Adam

Tullio Lombardo, c.1490-95

Overview

About This Work

Adam is a life-size marble sculpture by the Venetian Renaissance master Tullio Lombardo (c. 1455–1532), carved between 1490 and 1495 for the funerary monument of Doge Andrea Vendramin in Venice. Now housed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (since 1936), it stands as one of the most historically significant and artistically profound sculptures of the Italian Renaissance. The work is revolutionary for a single fact: it is the first monumental classical male nude carved in marble since classical antiquity—making it a watershed moment in Renaissance art history. Tullio carved Adam not from tradition or religious narrative alone, but from deep study of classical Greco-Roman sculpture. The figure's head is modeled on the Antinous type (the favorite of Roman Emperor Hadrian); the body derives from the Doryphoros of Polykleitos and the Apollo Belvedere. Yet this is not mere archaeological imitation. Tullio synthesizes multiple classical sources with a uniquely Venetian sensibility, creating a figure that is simultaneously classical in ideal beauty and profoundly humanistic in its psychological depth. Adam stands serenely, contemplative and thoughtful, at the moment before the Fall—not yet corrupted by sin, yet anxious in anticipation of temptation. The sculpture is the only surviving piece from the Vendramin monument bearing Tullio's signature, a testament to his pride in the achievement. It remains one of the most moving meditations on divine creation, human beauty, human frailty, temptation, and redemption in all of Western art.