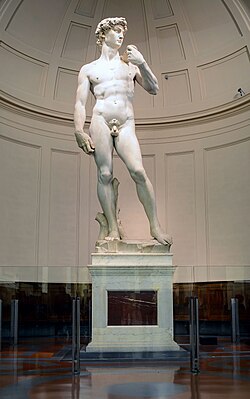

David

Michelangelo, 1501-1504

Overview

About This Work

David is a monumental marble sculpture by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), completed between 1501 and 1504. Standing 5.17 metres (17 feet) tall, it represents the biblical hero David as a colossal male nude figure in the moment before his battle with the giant Goliath. Originally commissioned as an architectural ornament for Florence Cathedral, it was deemed too magnificent for that purpose and was instead installed in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of Florence's government, where it became a symbol of the city's political independence and republican values. The David is recognized as one of the greatest sculptures ever created and a definitive masterpiece of the High Renaissance. It synthesizes classical ideals of beauty and heroism with humanist philosophy, creating a work that transcends its biblical origins to become a universal symbol of human potential and dignity. Michelangelo carved it from a single block of Carrara marble that had been damaged and abandoned by two previous sculptors, transforming what others considered a cursed stone into an immortal achievement.