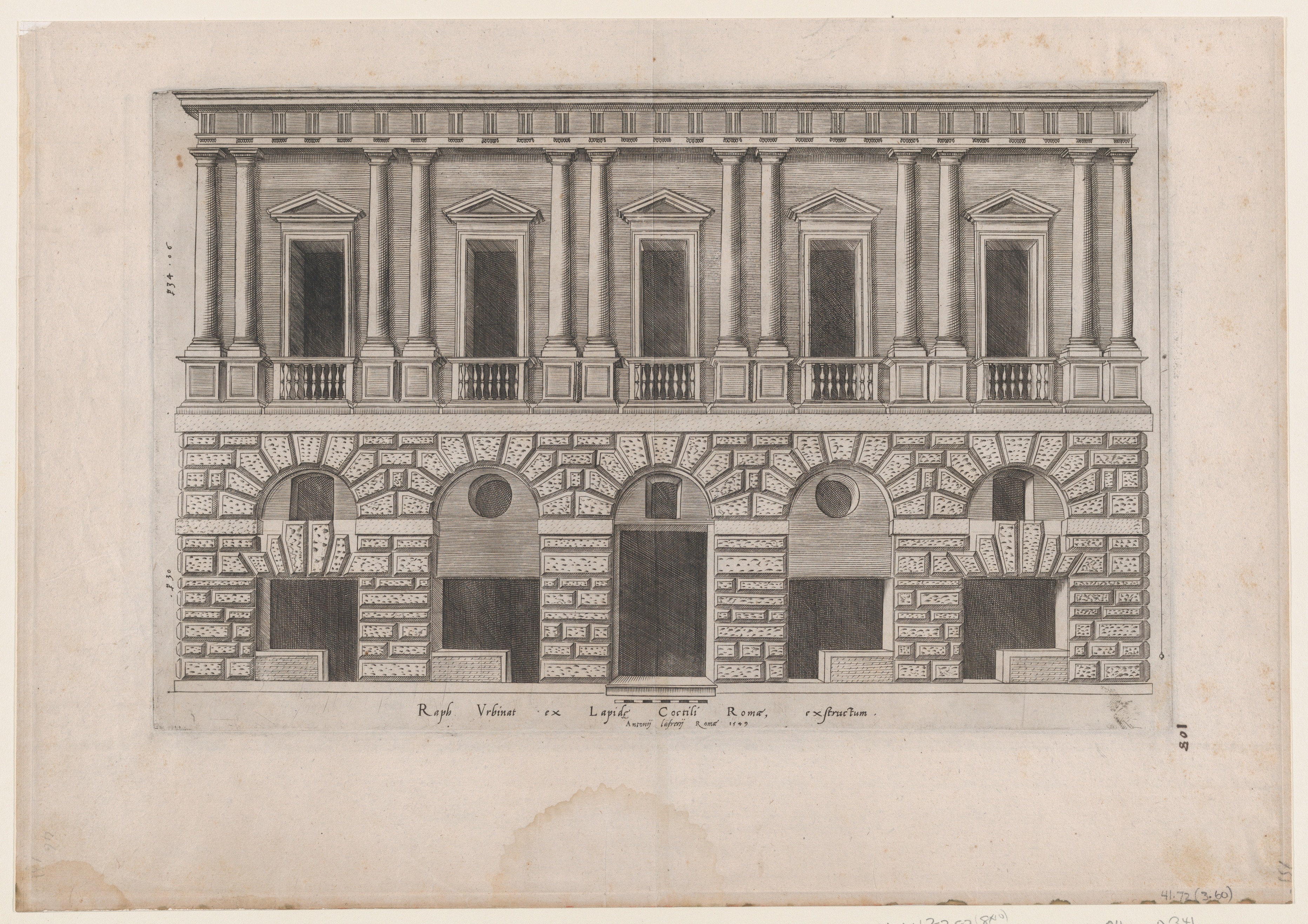

Palazzo Caprini

Bramante, c.1510

Overview

About This Work

Palazzo Caprini is a Renaissance palazzo in Rome designed by Donato Bramante and erected between approximately 1501 and 1510 for Adriano Caprini, an apostolic protonotary (high church official). The palazzo subsequently became famous as the "House of Raphael," after the great Renaissance painter Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio) purchased it in 1517 and lived there until his death in 1520. The building is now destroyed—it was demolished in the early twentieth century—yet it survives in historical consciousness and influence through contemporary engravings and drawings, most famously the etching by Antoine Lafréry and a partial sketch attributed to Andrea Palladio. Despite being destroyed, the Palazzo Caprini was "one of the most influential buildings of the Renaissance." It became the prototype for High Renaissance palazzo design throughout Italy and Europe, establishing conventions that would dominate domestic architecture for centuries. The building was "simple in its conception and harmonious in its proportions," yet this simplicity concealed profound architectural sophistication. It demonstrated how classical principles of proportion and order could be applied to practical urban residential needs, creating a building that housed shops at street level (generating income) while providing refined residential quarters above. The palazzo represents Bramante's genius for synthesis: it merged the rusticated ground-story arcades characteristic of fifteenth-century Florentine palaces (like the Palazzo Medici and Palazzo Pitti) with classical orders properly employed on the upper stories in a way no earlier building had achieved. The result was an architectural vocabulary that proved so effective and harmonious that it became a standard template for Renaissance and subsequent palace design.